Using their decades of experience in the oil and gas sector, three majors are moving forward with a project which will enable the transport of carbon dioxide captured from industrial sites in Norway and its storage in a reservoir below the seabed in the North Sea.

This landmark project is part of a global push for reducing carbon emissions, which is crucial in an effort to fight climate change.

Burning fossil fuels through energy production and industry emits carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere which then traps the heat and causes temperatures to rise, creating a chain reaction of effects which are jeopardizing the planet’s future.

We’ve created the problem and now we need a solution but the solution eludes us and it is getting ever more complicated due to differences in understanding, plain old denial, divided liabilities, and above all due to costs.

Not only have we already released too much CO2 into the atmosphere but we keep doing it due to our deeply rooted modus operandi. Should the emissions continue at this level, our hopes for a sustainable future might be extinguished sooner than expected.

With projects like this one in Norway, the change is imminent but there are still several years of work ahead before they are able to create results.

CCS precondition for achieving emission targets

One of the ways to tackle the global climate challenge is to capture the carbon and store it safely underground.

The carbon capture and storage process is considered a precondition for achieving climate targets set out in the Paris Agreement.

This global agreement aims to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions in an effort to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels while pursuing means to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees.

The idea behind carbon storage is simple. Just like oil and gas are held beneath the ground by the impermeable rock layers, the idea is for these formations to keep the stored CO2 beneath the ground as well.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), we captured 35 million tons of CO2 from power and industrial facilities in 2019.

However, this is not nearly enough to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement and IEA claims that CCUS in power is well off track to reach the 2030 Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) level of 350 MtCO2 per year.

Using oil & gas knowledge

In addition to being one of the pioneers and leaders in the oil and gas industry, Norway and its state-owned oil and gas company Equinor have been using its vast oil and gas knowledge and resources and working for years to curb its carbon emissions by capturing and burying carbon back to where it came from, underground.

Norway’s Sleipner project, located in the North Sea, was the world’s first offshore carbon capture and storage plant, which has been injecting CO2 into an underground reservoir, beneath the surface since 1996.

According to Equinor, the operator of the project, each year about 1 million tonnes of CO2 from the natural gas is captured and stored at Sleipner.

Norway is now getting a CCS project, which could become the first step to develop the necessary value chain for CCS.

In an effort to find a solution for a worldwide issue of CO2 emissions, three major oil and gas operators Equinor, Shell, and Total have joined forces and hammered out the Northern Lights project, which is part of the full-scale CCS project in Norway.

The three majors have recently made a decision to invest in the Northern Lights project in Norway’s first exploitation licence for CO2 storage on the Norwegian continental shelf and handed over plans for development and operation to the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

Their investment decision is subject to a final investment decision by Norwegian authorities and approval from the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA).

The initial estimated investment in the project amounts to about NOK 6.9 billion ($681.5 million), with over half of it estimated to go to the Norwegian contractors.

The project will create new activities and opportunities for industries and generate much-needed jobs at a time when the coronavirus pandemic and volatile oil market have become a serious threat to the employment of many oil and gas workers.

On an even bigger scale, Equinor’s Anders Opedal, executive vice president for Technology, Projects & Drilling, said that the project opens for decarbonisation of industries with limited opportunities for CO2 reductions.

“It can be the first CO2 storage for Norwegian and European industries, and can support goals to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2050”, Opedal added.

“Northern Lights is an example of the expertise and experience we have built up in the oil and gas industry being used in the development of new technology and new solutions that ensure sustainable use of energy. Hywind Tampen, which was just approved by the authorities, is another such example”, says Norwegian Minister of Petroleum and Energy Tina Bru.

Northern Lights plan

Once the authorities approve the plan for the Northern Lights project, the three players will form a joint venture and develop it in phases.

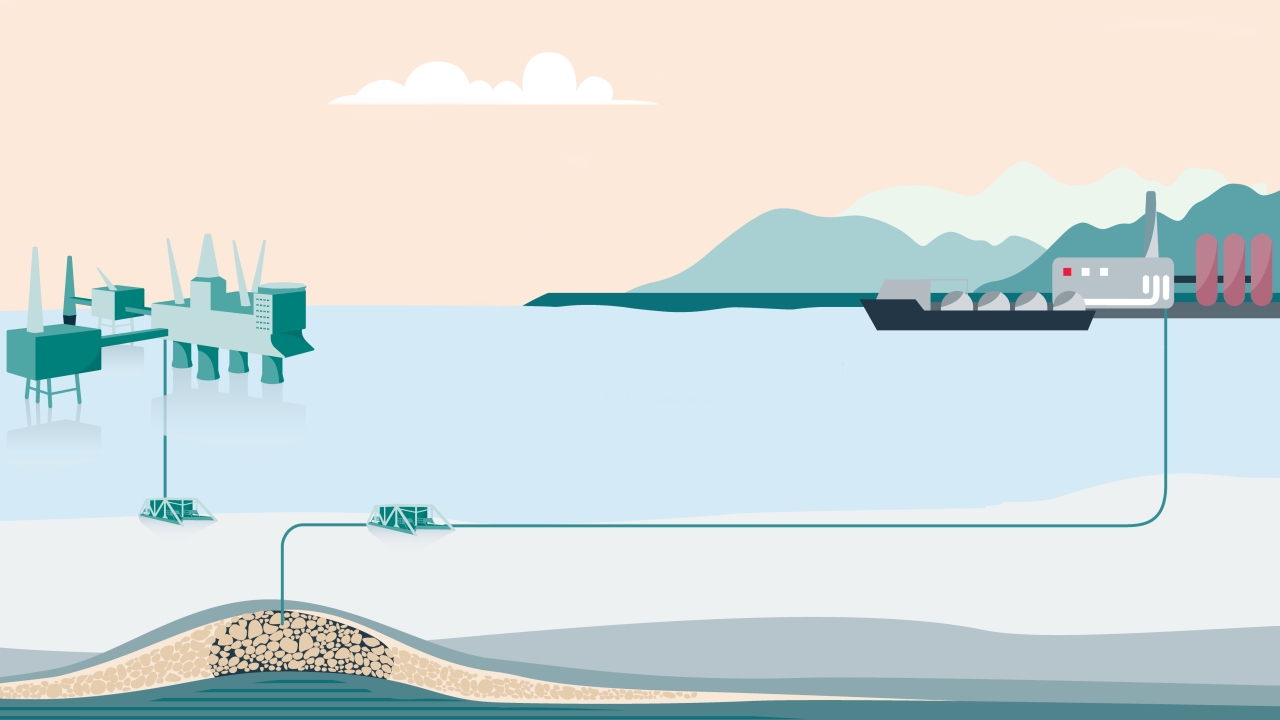

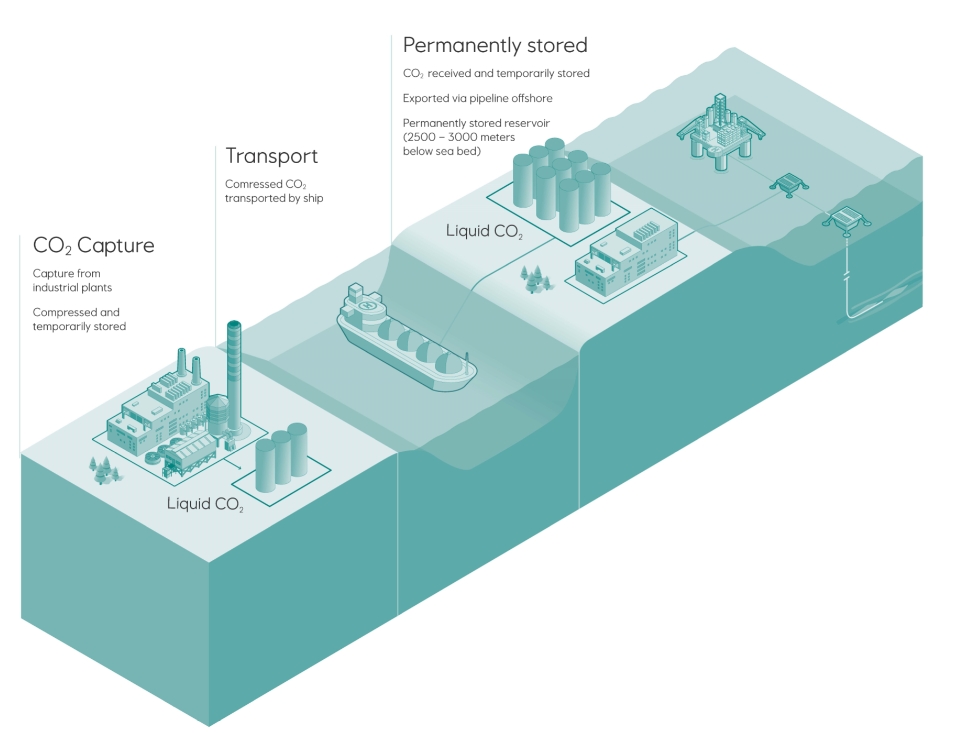

The project includes capturing CO2 from two industrial firms in Eastern Norway and transporting liquid CO2 to a terminal in Western Norway.

CO2 will be captured from Fortum’s heat recovery plant at Klementsrud in Oslo and Norcem’s cement factory in Breivik in the municipality of Porsgrunn.

Once the CO2 is captured onshore by industrial CO2 emitters, Northern lights will be responsible for transport by ships, injection and permanent storage some 2,500 metres below the seabed south of the Troll field.

The CO2 receiving terminal will be located at the premises of Naturgassparken industrial area in the municipality of Øygarden in Western Norway.

The plant will be remotely operated from Equinor’s facilities at the Sture terminal in Øygarden and the subsea facilities from Oseberg A platform in the North Sea.

Phase 1 includes the capacity to transport, inject and store up to 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year into the Johansen Formation.

The facility will allow for further phases to expand capacity and investments in subsequent phases will be triggered by market demand from large CO2 emitters across Europe.

If the project receives a positive final investment decision from the Norwegian Government in 2020, Phase 1 is expected to be operational in 2024.

It will have a planned operating period of 25 years and the storage capacity for phase one is just under 40 million tonnes of CO2.

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) said: “This is an important and unique project for the climate and for industrial development, both for Norway and in an international perspective”.

Estimates indicate, in theory, that the reservoir volume on the Norwegian continental shelf is sufficient to accommodate more than 80 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, a volume equivalent to 1,000 years of current Norwegian CO2 emissions, the NPD said.

A possible phase two of the development will increase capacity in the form of more storage tanks, increased pumping capacity, new quay plant and more injection wells.

The pipeline can handle increased capacity at the receiving plant as it is planned with a capacity of about five million tonnes of CO2 per year from the start.

If phase two is realised, the project will depend, among other things, on contractual access to CO2 for geological storage and sufficient storage capacity in the reservoir, the Norwegian ministry said.

What else is happening on this front?

Oil and gas majors have started getting on board the net-zero train with several of them pledging to become net-zero by 2050 or sooner.

BP last February said that this ambition was supported by ten aims, five to get BP to net-zero and five to help the world get to net zero.

The first five aims include net-zero across BP’s operations on an absolute basis by 2050 or sooner; net-zero on carbon in BP’s oil and gas production on an absolute basis by 2050 or sooner; 50% cut in the carbon intensity of products BP sells by 2050 or sooner; install methane measurement at all BP’s major oil and gas processing sites by 2023 and reduce methane intensity of operations by 50%, and increase the proportion of investment into non-oil and gas businesses over time.

Shell’s plans include an ambition to be net-zero on all the emissions from the manufacture of all its products (scope one and two) by 2050 at the latest.

It will also include accelerating Shell’s Net Carbon Footprint ambition to be in step with society’s aim to limit the average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

This means reducing the net carbon footprint of the energy products Shell sells to its customers by around 65 per cent by 2050 (increased from around 50 per cent), and by around 30 per cent by 2035 (increased from around 20 per cent).

Furthermore, Equinor in January 2020 launched new climate ambitions to reduce the absolute greenhouse gas emissions from its operated offshore fields and onshore plants in Norway with 40 per cent by 2030, 70 per cent by 2040, and to near zero by 2050.

By 2030, this implies annual cuts of more than 5 million tonnes, corresponding to around 10 per cent of Norway’s total CO2 emissions.

Total has also recently committed to becoming a net-zero emission company for all its European businesses by 2050. It is important to notice here that this does not apply to its global activities.

Microsoft’s carbon negative plan

It is also worth mentioning that the IT giant Microsoft in January 2020 revealed its ambitious plan to become a carbon negative company by 2030 and by 2050 to remove from the environment all the carbon it has emitted since it was founded in 1975.

Being carbon-negative means that Microsoft plans to remove more CO2 than it emits and carbon neutrality means removing an equivalent amount of carbon as the one being emitted into the atmosphere.

These are only some of the players which have revealed their goals and plans for a carbon-neutral future, but there’s theory and then there is practice and the result of these efforts still remain to be seen.

The post Using oil and gas know-how to develop CO2 capture and storage project amid push for lower emissions appeared first on Offshore Energy.

Want to know more about what CCS is and how it works? Sverre out at the Sleipner field shows and explains more here:

Want to know more about what CCS is and how it works? Sverre out at the Sleipner field shows and explains more here: